As you may have seen, there has been a great deal of commotion in the news recently about the new and possibly dangerous COVID-19 variants.

But, as with all things, it is best to analyze the data and assess the facts before concluding the level of threat the new variants pose to our health.

Firstly, let’s look at what causes viruses to evolve into new strains.

In the life cycle of a viral outbreak or virus in general, it is entirely normal for many evolutionary shifts in genetic sequence.

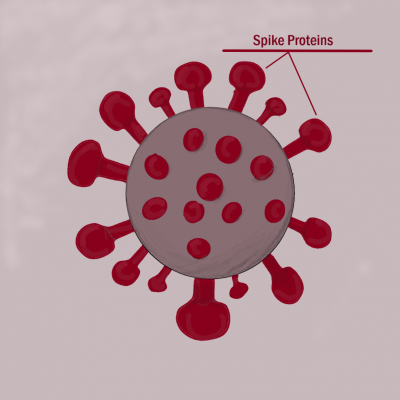

The UK and South African Covid variants are precisely this, an alteration of a spike protein (also known as a peplomer) on the covid-19 molecule itself.

Graphic via Anne Ahern

As one may expect, spike proteins are the pointed crown-like (hence, “corona” virus) knobs visible on the outside of a covid-19 molecule.

When viruses replicate themselves, they are essentially re-generating a small book’s worth of genetic sequence.

Like an elaborate game of telephone, many minute changes in the genetic sequence pop up, eventually causing the virus to mutate.

Usually, these mutations have little to no effect on the function of the virus.

However, due to the sheer volume of alterations, there are bound to be a few that do end up noticeably altering the virus.

Whether this noticeable way is positive or negative for us or the virus is a toss-up, as discussed in an article by National Geographic.

The UK variant, variant B.1.1.7 (there seem to be multiple known variants, but more on that later), is believed to have caused the January spike in UK cases.

Believed to be a descendent of a mutation brought about by the deletion of spike protein components H69 and V70, B.1.1.7 is currently under priority observation in the UK as preliminary scientific publishing identifies the mutation as a cause of increased transmission.

In plain English, this means that we aren’t entirely sure yet, but the new UK mutation seems to make the virus much easier to catch and transmit.

So, what does this mean for death and long-haul infection rates?

Overall, we are not sure yet.

The variants were only discovered to be prominent in the population under a month ago, which means there hasn’t been enough time to observe and report trends properly.

The South African variant is believed to have multiple spike protein changes and is reportedly affecting the protein binding ability of the COVID-19 molecules.

Known as B.1.351, the Wall Street Journal reported the South African variant to be around 50% more contagious, similar to the UK variant.

Not only this, but the change in the binding structure has shown a change that allows the virus to infect mice.

In a non-peer-reviewed article published by BioRxiV, the vaccines available were shown to be more than 90% effective in the UK variant (specifically the H69/V70 mutation), but closer to 60% effective against the South African virus mutation.

However, the article above also discussed that the 0.81 and 1.41-fold difference between the variants and the strain used in current vaccine technology is much lower than the 4-fold variation that triggers the creation of a new flu vaccine, indicating the change- while not insignificant- is minute.

Though the vaccines have been shown in preliminary science to be less effective against the variants, specifically the South African variant, many variants’ genetic code remains similar to if not the same as the initial virus.

This gives us hope for possible booster shots (much like the flu) when caught up with the initial vaccine doses.

Additionally, it has not been proven that the new variants are more dangerous, simply more transmissible.

Overall, the same advice applies to fighting the new and more slippery variants as applied to the original virus.

Remain firm in these final months leading up to the first administration of a COVID-19 vaccine, stay responsible, stay safe and review the science.