Young generations have grown up in an America in flux. We are no longer fixed to a sense of American security or status quo, instead constantly bracing for rapid trend cycles and strong political dissonance.

Religious participation has nearly halved in the past 50 years. Young adults are on screens for over 7 hours per day. More than 60% of Americans are living paycheck to paycheck. Despite constant innovation in technology and diversity, our country is down and out, disconnected, and suffering from national narcissism.

How do we band together? How do we break through our epistemic bubbles, log off, and find unity despite the forces attempting to pull us apart?

For one, we are drawn to consume media collectively. Through years of struggle and a pandemic that nearly wiped them out entirely, movie theaters continue to bring out major audiences from all aisles and poles of our political and socio-economic spectrums.

Six films have reached the billion-dollar mark since the pandemic and Netflix’s eight most-watched seasons of original TV premiered after the COVID lockdown. The two most recent Superbowls garnered the most U.S. viewers of any televised event in history. When nothing else seems to, entertainment continues to bring Americans together in shared positivity.

Yet, audiences, though bonded in consuming the same media, have been put into a prime position for polarized, chauvinistic, and inflammatory behavior similar to much of America’s political and social climate.

Films are increasingly tied to divisive political ideologies, film reviews and rating have now been popularized on criticism-focused social media like Letterboxd, and media in general seems to have made audiences into pawns to sway and provoke. Quality and integrity are now merely a second thought.

When controversies concerning creators come into the mix, the effects are pandemonious. While the morality of some controversies such as the years of abuse and exploitation by now-imprisoned producing mogul Harvey Weinstein is easier to discern, “cancel culture” has become a highly malleable concept to be manipulated by unqualified, disconnected, or vengeful individuals on an array of worthy and unworthy targets.

Take last year’s widespread backlash against Doja Cat for her unsavory remarks about fame and fans or the massive outcry against Sam Levinson’s transgressive HBO mini-series The Idol. In both cases, audiences took time to vocally push back against behaviors they deem inappropriate or content they find displeasing.

In a media climate focused on providing endless vibrant content choices, it’s curious that these individuals don’t simply disengage from these works and creators and choose media that better fits their objectives.

There are more intense examples of this phenomenon, including R. Kelly, the iconic R&B singer and multi-instrumentalist who is now in prison for child sex crimes. On the other hand, Woody Allen, one of film history’s greatest auteurs, has been blacklisted from Hollywood after 1992 accusations by his adopted daughter of sexual abuse and the widely publicized decades-long relationship between Allen and his step-daughter, Soon-Yi Previn.

In the case of Kelly, “cancel culture” and public outrage surrounding legal proceedings against him did no disservice to his success, and of course offered no consolation to his victims. According to Rolling Stone, Kelly’s album sales were up 500 percent after his trial’s guilty verdict.

For Woody Allen, even legal proceedings determining his innocence in the charges against him couldn’t grant his career mercy, forcing him to continue his filmmaking career overseas with no attention from major American festivals, awards, or media. The morality of his personal relationships is questionable, no doubt uncomfortable, but he acted within set boundaries in the eyes of the law.

American audiences have been instilled with two major traits with the rise of the internet. They have been given unprecedented power in determining the morality, popularity, and legacy of content and individuals, and they have assumed an attitude of righteousness, each individual pining for justice on their own ideological scales.

And so, we are faced with the eternal question in digital activism and media criticism: should we separate the art from the artist?

First, we must examine the effect of boycotting artists in general. Can refusing to buy an album, to see a movie, to support a cause make an external difference?

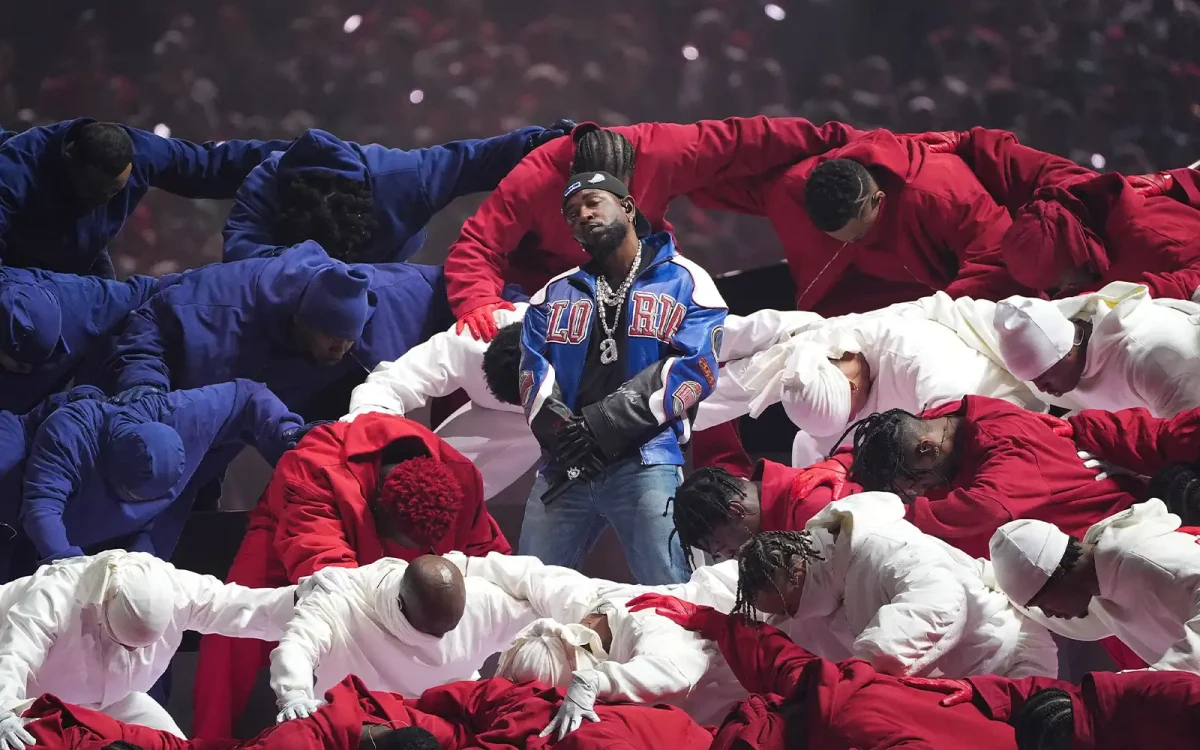

Using Kanye West’s newest album, Vultures 1, as an example, someone refusing to listen must understand that their lack of participation, though maybe fueled by a denial to support bigotry, is working only on an internal emotional level. When they continue to listen to, say, Playboi Carti, Guns and Roses, or even Tupac, who have all garnered domestic or sexual assault allegations, their “activism” seems to lose its weight.

From the civil rights movement back to the American Revolution, the practice of pushing back against the injustice and abuse of power in America has worked to create tangible change. Perhaps the availability of damning information on public figures is too extensive now to tackle, perhaps our attitudes on crimes and injustices have simply changed. Whatever the case is, in the digital age, boycotting and blame only comes across as futile and shrill.

One’s personal answer to this question can’t unilaterally define their politics. If an individual decides to listen to Vultures 1, does that make them complicit in West’s record of antisemitic remarks? If they are blind or ignorant to his recent outbursts, does merely offering numbers and fractions of pennies to his streaming success make a listener a willing supporter of his ideologies?

I see their consumption of Kanye West just as morally questionable as, say, their consumption of Crunch bars, their choice of a Hyundai car, or their use of an iPhone. Just one bar, just one phone, just one sold unit still contributes to corporate offense against our freedoms and future. But never have I heard an individual called a supporter of child labor for consuming Nestle’s or Apple’s goods.

We could take it further, calling patrons of Burger King, McDonald’s and Starbucks planet-destroyers for supporting an industry that contributes to 49% of all litter. Say what one will about Chick-Fil-A’s politics, but their use of styrofoam is no doubt objectionable in this stage of climate change. But are we so rigidly asked to separate these products from their producers?

I would offer a resounding “no”, and for understandable reasons. While we can throw our plastic waste in fast food garbage bins and forget about our dirty deeds, art is in our face, often asking us for our most dramatic opinions.

The nooks, crannies, and reverberating social effects of our entertainment consumption cannot be hidden and a society of criticism and political strife have trained us to vomit our shallowest and most preliminary opinions and impulsively jump to the side of the aisle we deem closest to our beliefs when challenged by art.

One must also examine the reason they choose to consume media and the lens through which they view it. Does an individual want to be merely entertained? Do they want to explore society and history through art? Do they seek art hoping to enrich their life and identity?

In each of these circumstances, displacement between the audience and the artist varies. The art is experienced in a flexible context that elevates the priority of entertainment, education, or transformation over any personal opinions about the artist behind the work. In the connoisseur’s eye, this is how it should be.

Yet art is no longer judged or discussed on its merits, instead analyzed for its adherence to social and political norms and whether its creators’ ideological and interpersonal histories clash with our own. Quite possibly high-quality media becomes a no-go for audiences who deem themselves morally incongruous with the minds behind the work.

Even artists like Ariana Grande, whose greatest recent offense is a love affair with a married man, become quick pariahs among audiences whose horses are high and morals are “untarnished”.

Besides art and artists, there is a crucial question many purposely ignore: can we separate the art from the audience?

In a period where we refuse to be guided by religious doctrine and have crafted political perspectives too highly tailored to unite more than a simple majority behind a presidential candidate, do we have the individual media literacy and social awareness to make our own decisions on our media consumption?

I would hope that, despite social media’s manipulation of our values, the majority of audiences still have the moral compass not to embrace transphobia while consuming Dave Chapelle or J.K. Rowling’s work, and not to endorse pedophilia while watching Rosemary’s Baby.

If an individual is seeking to understand modern art through an investigative sociological lens, consciously engaging with problematic work instills it with a new historical value independent of artists’ intentions or backgrounds. If any of this consumption makes an individual uncomfortable or offended, I would hope that they have the self-respect to steer away from it without imposing their own ideologies on other more neutral audiences.

American law and order has done a decent job putting an end to true offenders in the entertainment industry and likely still has much work to do. Guidelines and policies on the production side of our entertainment continue to update with the times to ensure our films, music, and other media are produced legally and ethically.

Clickbait, ragebait, thumbnails, and cancellations may offer catharsis against deemed cultural offenders, but the merit of great art seems to dictate its importance and legacy despite–or perhaps elevated by–even its most questionable creators.