The 2024 Academy Awards was hosted on Sunday, March 10. This year’s ceremony was groundbreaking for a number of reasons. For the first time in history, three foreign-language films were in the running for Best Picture. An unprecedented three films directed by women were also up for the same award. Steven Spielberg made history this year as the individual with the most Best Picture nominations ever, nominated this year as a producer of Bradley Cooper’s kaleidoscopic and Leonard Bernstein biopic, Maestro.

Also unprecedented and sparking the most buzz was the Academy’s new diversity and inclusion rules, first proposed in September of 2020. The set of regulations dictates a film’s eligibility for the Best Picture award based on the meeting of two of four inclusivity standards. Competing films must also complete the Academy’s Representation and Inclusion Standards Entry (RAISE) form.

The four standards cover on-screen representation and narrative inclusion. Films can comply with the standards by casting underrepresented groups, featuring storylines centered on marginalized individuals, and hiring artists from underrepresented populations in leadership roles in costumes, producing, and other departments.

The flexibility of the rules allows a film like Oppenheimer, which was this year’s Best Picture, to remain eligible. The film features an entirely white cast and its narrative never veers away from its white male protagonist, but it has an Asian executive producer, a female costume designer, and production company officials from groups historically underrepresented in the film industry, therefore complying with the guidelines.

Still, the rules have received criticism from diverse industry faces for years leading up to their implementation this awards season.

A week after their announcement, Oscar-winning Mexican filmmaker Alfonso Cuarón spoke about the policies in IndieWire.

“The interesting thing is that it’s not coming naturally. Everybody has to respond to outside pressures,” he said. “That’s a little bit disappointing — that it needs to go through rules and regulations for things to happen when it should just be a natural process of societal evolution that apparently is not happening.”

Interestingly, for four years before the 2020 announcement of these rules and during the three ceremonies since, all Best Picture winners adhered to the guidelines now in effect.

The larger question appears to be whether these divisive regulations will measurably improve industry conditions for its most unsupported groups and why they were deemed necessary.

Across industries, the marginalized and underrepresented groups are being embraced through diversity mandates, but these seem to come too little too late to truly stand for the liberation of subordinated groups. Only in 2018, after three waves of modern feminism and the #MeToo movement, did California pass a mandate requiring the appointment of at least one woman to every publicly traded corporation’s executive board. This rule was eventually struck down in 2022.

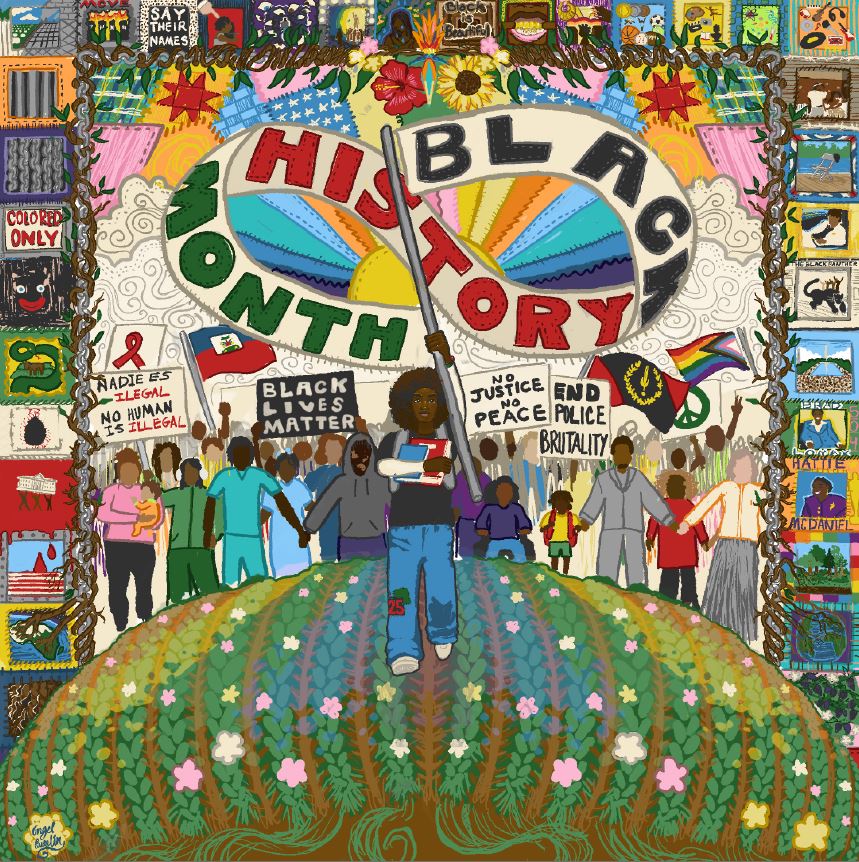

On the other hand, The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences rushed to invite an exponentially more diverse population to their membership and announced these new rules only after years of white-male-dominated awards seasons, including an infamous year of all-white nominees in 2016, and months into a socially catalytic summer of Black Lives Matter protests.

The new rules may appear to some as an integration of harmful identity politics into an ostensibly meritocratic industry celebration. To others they’re seen as a necessary step forward to ensure that all individuals have a chance to be honored with awards in the arts.

Most important, however, is the notion that these changes have been seemingly sparked by entirely extrinsic forces to the Academy or film industry at large. The controversy surrounding them seems to be a feature, not a bug, of their purpose.

Announcing mandates that wholly agree with already-popular standards of film production and Academy taste seems merely a tactic to cover the Academy’s bases. It is perhaps just another effort to save their reputation before the already declining viewership of the esteemed ceremony is exacerbated by the glaring equity issues it has swept under the rug.

Though touted as progressive policies, these regulations can be grouped together with the proposed – and recently scrapped – “Best Popular Film” category and decision to announce more niche technical awards during commercial breaks. All are just integrity-compromising attempts to stimulate viewership. The decision to publicly release these guidelines, feels

more like a PR stunt generating discourse off of venomous modern political rifts than an admission of wrongdoing or a hope for true change.

This year, four of the 10 nominees for Best Picture centered on female storylines. Eight nominated producers were women. While a measurable increase in diversity can be seen over the last decades of Oscar nominations regardless of firm and official nomination guidelines, the celebration of equity must be held in tandem with the honoring of timeless, resonant, and technically robust films vying for awards.

Say what one will about the worthiness of each Best Picture nominee’s recognition this year, but not only did some achieve a cohesive cinematic vision more successfully than others, some more diverse choices incorporated their inclusivity in far more daring and stimulating ways than their opponents.

Not all representation is created equal, and to correct the inequalities and injustices of film history, films must not only be crafted by and showcase those whom Hollywood brushed over in decades past, but must be created with humanity, integrity, and attention. The Academy diversity rules may not drastically improve the state of equity in cinema or the quality of diverse

stories presented to audiences. If anything they are a wake-up call. In the film industry and across the country, cultural change for the better – in both quality and equality – must and has always started from the ground up.