Comfort Women: A History

March 31, 2023

From 1932 to 1945, there was a high number of women who were forced to provide sexual services to Japanese soldiers by the Japanese Imperial Army during its time of occupation in nearby countries and territories such as Korea, China, and the Philippines. The term “comfort women” is the translation of the Japanese word, ianfu (慰安婦). Although the actual amount is still debated and often varies from one study to another, the estimate that is often agreed upon typically ranges from 50,000 to 200,000 victimized women.

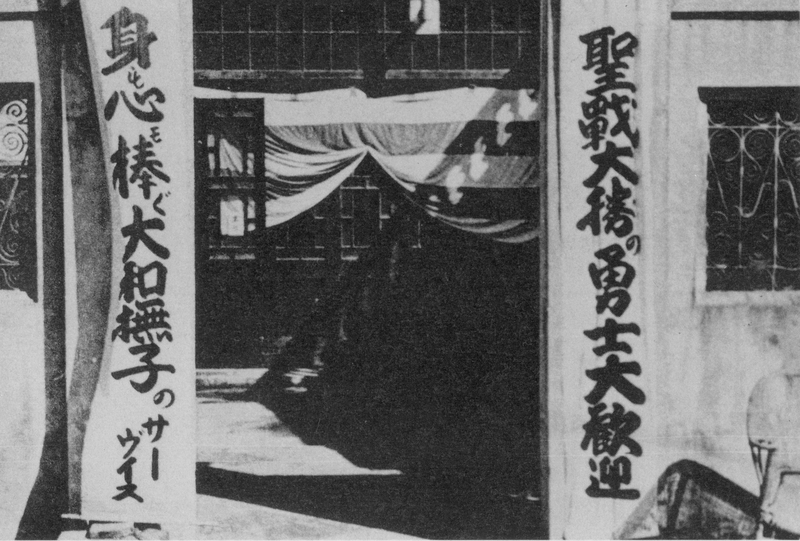

The original objectives of the “comfort stations” were to prevent wartime rape, contain venereal diseases, enhance morale, and give an outlet for the Japanese soldiers. Most cases of comfort woman recruitment involved deception, such as middlemen luring women for employment or higher education opportunities or kidnapping. Once the women were enlisted, they were immediately put to work by sending them off to local or overseas military bases, with a significant number of these women being of minor age at the time, with the youngest being twelve years old. The conditions of what they faced on a daily basis were harsh, as women were subjected to daily assaults, threats, and even death if they were not willing to abide with what was expected of them to do and to follow.

Women were being enslaved and forced into providing sexual intercourse for the pleasure of Japanese soldiers; thus, more often than not, most disregarded their personal freedom and autonomy and were viewed as servants, objects, and anything of the like. Despite the initial goal of reducing wartime rape and preventing diseases, it only increased with the presence of the comfort stations as victims were violated and raped throughout the day and were regularly tested for sexually transmitted diseases and infections by the Japanese military as they wanted to keep their armies healthy and the stations under strict regulations.

By the end of World War II, most of the comfort women had been executed. Those who did survive were frequently subjected to traumatic consequences on multiple levels: physically, mentally, emotionally, socially, and psychologically. Additionally, they were also shunned by their respective families, friends, and societies during the aftermath of it. Those who were stationed abroad were unable to return to their home countries as they lacked the means to do so and simply stayed instead.

Many scholars who have been actively researching this event have argued that the term “comfort women” is a euphemism coined by the Japanese military to alleviate the severity of the crime and prefer to use the seemingly more appropriate term “military sex slaves” instead. They have also considered this to be the largest case of modern human trafficking and sexual slavery conducted by a governmental entity.

However, the topic of comfort women still seems to cause controversy and heated discussions in the preoccupied areas, as there have been numerous instances where the victims, their families, and organizations have stepped in and spoken up about their experiences and requested an apology and recognition for the crimes that the Japanese government has inflicted on them and to hold their nation accountable. Though most, if not all, were eventually dismissed and even denied such actions, labeling them as “voluntary prostitutes” in their defense. In recent years, right-wing Japanese political parties have even taken the topic out of textbooks, making it nearly impossible for students to learn this part of their history accurately (Shin, 2021).

There have been notable women who have chosen to share their experiences with the public and have even advocated to prevent such atrocities from occurring in the future. Kim Hak-Sun, a Korean comfort woman who became a human rights activist and advocated against wartime sex violence and sex slavery, was one of them. She was barely 17 years old when she was abducted and taken to a comfort station in China by the time of the war. She could still recall incidents of rape and sexual assault that she faced on a daily basis and being forced repeatedly to escape whenever she tried to escape. In 1991, at 67 years old, she gave her first testimony about the horrors of her experience. After this, many of the victims came forward, hailing from countries such as China, the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, Australia, and the Netherlands. A year later, a protest was held every Wednesday in South Korea just outside the Japanese embassy after a surge of 238 different accounts from other comfort women came to light (Choi, 2021).

Another was Jan Ruff O’Herne, a Dutch-Australian woman who kept her silence as a comfort woman but decided to campaign against wartime rape beginning in the 1990s until her death in 2019. She had served as a comfort woman for three months and was warned that if she shared about her experiences, she and the rest of her family would be killed. She kept her silence until 1992, when she became the first European woman to speak up about her experience (Seelye, 2019).

In South Korea, there is a nursing home, the House of Sharing, that has dedicated itself to being a home to survivors since its foundation in 1992 by private individuals and a Buddhist organization. Additionally, it offers an opportunity for people to interact with the survivors and be educated about the history behind it (Bradley, 2019), as well as art therapy for the residents, who are also able to share their artwork in a built-in exhibit hall.

Despite the threats they have faced after the war, there are more stories being shared by the survivors since the first testimony led by Kim Hak-sun in 1991. The House of Sharing hosts events and exhibits to showcase their cause, and the information can be accessed through their website, www.nanum.org. The site is Korean and offers an English translation. Jan Ruff O’Herne wrote a memoir in 1994 entitled “Fifty Years of Silence,” in which she goes into more detail about her encounters with her life prior to the war and the gruesome accounts of her time as a comfort woman while being separated from her loved ones. Finally, the New York Times has published an article written by Sang-Hun Choi entitled “Overlooked No More: Kim Hak-soon, Who Broke the Silence for ‘Comfort Women,” which entails the first testimony led by Kim Hak-Sun and the effects of what happened afterwards.